Meet the Filmmakers

-

Julie Ha

DIRECTOR

Julie Ha’s storytelling career spans more than two decades in ethnic and mainstream media, with a specialized focus on Asian American stories. She was former editor-in-chief of KoreAm Journal, a national Korean American magazine. Free Chol Soo Lee, which premiered at the 2022 Sundance Film Festival, is her first documentary film.

-

Eugene Yi

DIRECTOR

Eugene Yi is a filmmaker, editor, and writer from Los Angeles. His editing work has been in Berlinale, Tribeca, and The New York Times. He was a contributing editor for KoreAm Journal, a national Korean American magazine.

-

Su Kim

PRODUCER

Su Kim is an Academy Award-nominated and Emmy®️ and Peabody Award-winning producer. Her films in release include Bitterbrush; the OSCAR®️ and Primetime Emmy®️-nominated Hale County This Morning, This Evening; and Midnight Traveler.

-

Jean Tsien

PRODUCER/ EDITOR

Jean Tsien is a documentary editor, producer, and consultant. She received two Peabody Awards in 2021: for executive producing the PBS series Asian Americans; and for producing 76 Days, winner of a 2021 Primetime Emmy®️. She has received Sundance Institute’s 2018 Art of Editing Mentorship Award and DOC NYC’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

-

Sona Jo

PRODUCER

Sona Jo produces feature documentaries about conflict, war, trauma, and women. Her films include 206: Unearthed, winner of the Best Documentary Award at the 2021 Busan IFF, and Coming To You, winner of the Best Documentary Award at the 2021 Jeonju IFF. She is a board member of the Korean Independent Producers & Directors' Association.

-

Sebastian Yoon

NARRATOR

Sebastian Yoon earned a Bard College bachelor's degree in Social Studies through the Bard Prison Initiative in 2017. Now an Acting Program Officer at the Open Society Foundations, Sebastian is a member of the Democracy Team, working toward building an inclusive, multiracial democracy and leading a portfolio to politically and civically empower Asian American Pacific Islanders (AAPIs).

A STATEMENT from the directors

“We knew we had to dig in and excavate this singular story, in all of its complexity and messiness. This story needed a release.”

The seeds of this film were planted in December of 2014, at the funeral of Chol Soo Lee, though we didn’t know it at the time. One of the directors was there to write an obituary for a magazine, but she also wanted to comfort her longtime journalism mentor, K.W. Lee. It was his series of stories that had helped launch a landmark social movement to free Chol Soo Lee from prison 40 years earlier. K.W., who had become a father figure to Chol Soo, never expected to outlive him and was in terrible anguish.

He was joined at the modest Buddhist funeral by a few dozen people; many of them were the activists who had rallied to Chol Soo’s side while he was in prison and tried to support him through his turbulent post-release life. They were mournful, but the emotion in the space felt like it went beyond grief. There was a palpable heaviness.

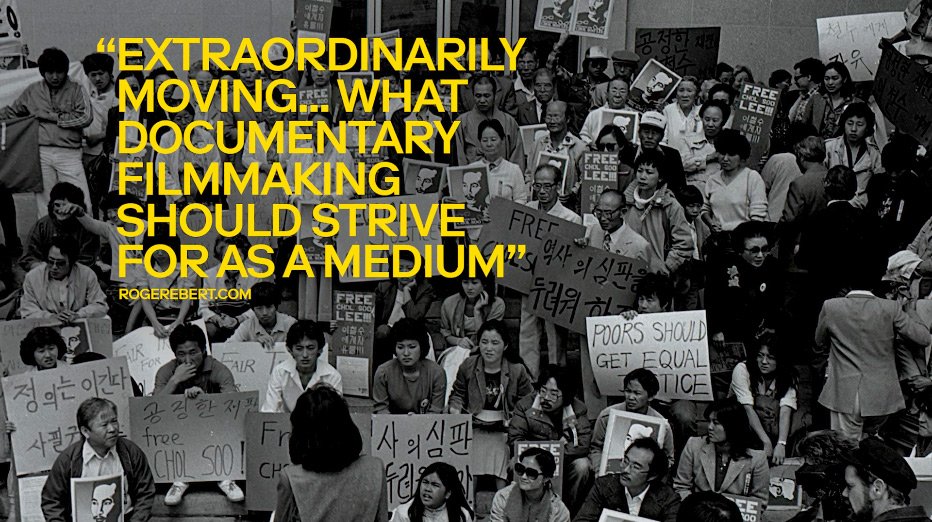

One activist read a letter to Chol Soo, saying she would forever regret not doing enough to save him. Another, who was inspired by the case to become a public defender, said Chol Soo did more for him and the other activists than they did for him. Their depth of humanity, compassion, and responsibility to this man was moving. They had, after all, given so fully of themselves to a stranger, in a six-year-long social movement that would boldly stand up to the American criminal justice system, overturn two murder convictions, and get him freed from death row. And yet, when the mourners chanted, “Free, free Chol Soo Lee,” this one-time defiant and passionate cry for justice now felt like an elegiac lament.

Then, K.W. Lee, clutching the Buddhist monk’s walking stick Chol Soo had carved for him out of a tree, stood up and cried out, “Why is this story underground after all these years?” He lamented that this history had become all but forgotten, not even taught in university Asian American studies classes. Perhaps it proved too messy a tale for the “model minority” to embrace. Whatever the reason, it was at risk of being lost to history.

As Asian American journalists and storytellers, inspired and mentored by K.W. Lee, we could not allow that to happen. We knew we had to dig in and excavate this singular story, in all of its complexity and messiness. The racism, the injustice, the trauma, the heroism, the idealism, the burden, the pain, the regret. The heaviness. This story needed a release.

Indeed, we see that the process of making this film has provided some kind of catharsis for those who lived this story and genuinely cared for Chol Soo, not just the symbol, but the man. His life was so hard for so long, even after his triumphant release from prison. And it's been the source of a deep ache for many of his most devoted supporters because they thought they had fought and won against the all-powerful criminal justice system in this David-vs.-Goliath struggle. As one of them said, it was like a fairytale at first. But then, their hero would suffer even more in so-called freedom. The act of having them remember and reflect on Chol Soo Lee, the complicated man who carried wounds from his very birth and who felt like he could not live up to the movement’s expectations of him, has provided some element of healing and closure. One activist who saw the film told us she feels a heaviness has lifted from her chest.

We’d like to believe it carries a sense of release for the spirit of Chol Soo Lee, too. Although he felt burdened by the weight that came from being the symbol of a movement, he also tried mightily in his final years to honor his supporters by speaking publicly about the Free Chol Soo Lee movement, so that there could be a lasting legacy. He recognized the importance of people today learning that at one time, Asian Americans—young and old, politically conservative and politically radical—united in unprecedented fashion around a poor Korean immigrant street kid, who was by his own admission no angel. And yet they deemed him worthy of their time, attention, love and care.

Ultimately, we believe he longed to return this humanity given to him by sharing his struggle. This film—which notably like the movement itself took six years to reach its goal and was made possible thanks to an entire chorus of dedicated individuals including our producers Su Kim, Jean Tsien and Sona Jo—became a vehicle to help him to do that. Our narrator Sebastian Yoon, who drew on his own lived experience of incarceration, no doubt infused his voicing of Chol Soo’s words with a heart and honesty that is deeply felt.

We hope our film allows Chol Soo Lee to find agency, to tell his own story, to speak his truth—and finally, to be free.